The Wandering Lens

Introduction | Writings | Photographs | Contact |

NEPAL

Deb Mukharji 16.12.2008.

(updated 31.1.2009)

The relations between India and Nepal are commonly described as unique. The open border, national treatment granted to the nationals of each other (even though there is imbalance in how each country implements the facility) and the long existing familial links at various levels, do underline the extraordinary relations between the two sovereign states, though these have not always translated into closeness in political relations. India has a direct interest in the development of water resources in Nepal. Besides industrial ventures, this is one area where Indian involvement in terms of collaboration with Nepal is possible. There are areas where developments in Nepal could impinge negatively on India's security. These may be described as areas of concern which are no less matters of vital Indian national interest, even if our ability to influence outcomes may be limited. It is acknowledged in Nepal that relations with India are a major determinant of its internal politics. It is also a converse reality that Indo-Nepal

The paper will seek to identify the various issues and mutual perspectives, with suggestions for the future. The intense and pervasive nature of the relationship and geographical imperatives does not permit a limited time span for consideration. Interests and concerns would remain constant, the emphasis perhaps altering even as scenarios may change. And what makes Indo-Nepal relations so complex, and often confusing, is that it is at the same time a matter of foreign policy between two sovereign states while being simultaneously seen by many in both countries as being in the nature of being a family matter. The achievement of India's national objectives has necessarily to bear in mind the interests of Nepal.

There is a running thread of permanence in India's interests and concerns vis-à-vis Nepal and what is

valid today will be so for the foreseeable future.

The subject will be considered under the following main topics:

1. Nepal - Current internal developments

2. Scenarios

3. Indian interests and concerns

4. Nepal's interests/concerns/perceptions vis-à-vis India

5. Indian assets

6. Building blocks for the future

Nepal is in a process of churning and transformation. For long, the valley of Kathmandu defined Nepal. This is no longer so. Ten years of Maoist insurgency inflicted great pain on Nepal. Translated into Indian figures, there would have been half a million killed in an insurgency in a decade. The conflict also caused many Nepalis to look inward to understand what had gone wrong. Hitherto marginalized elements have found a voice. The results of the elections to the Constituent Assembly were unexpected. It has put on the Maoists the onus of delivery on their promises. But the parties defeated seem yet to be reconciled to the changed scenario.

The term 'new' Nepal has now become commonplace. It is necessary to define this. Nepal has been looked upon as a part of South Asia. While geographically so, in terms of society and polity, the people of Nepal were kept back a century or two. This was in the interests firstly of the Ranas, who ruled Nepal for a century

'New' Nepal can be said to date from the people's movement of April, 2006. It was an assertion of people's power and aspirations supported by, but not dependent upon, political parties. The marginalisation of the monarchy and the move towards elections for a Constituent Assembly arose from this movement. It was an assertion of people's power unprecedented in South Asia. It would be an error to see this as being exclusively Maoist in nature. If the Maoists were a catalyst, so too, ironically, was the king in his quest for absolute power.

One of the major consequences of the

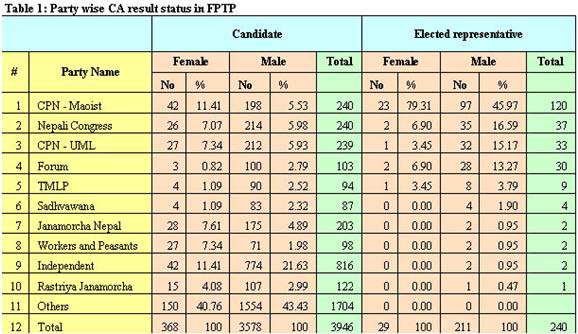

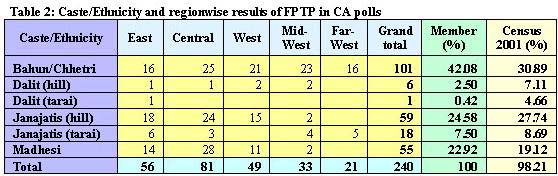

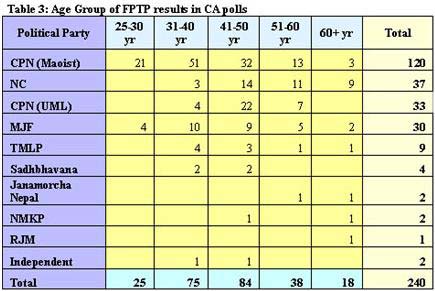

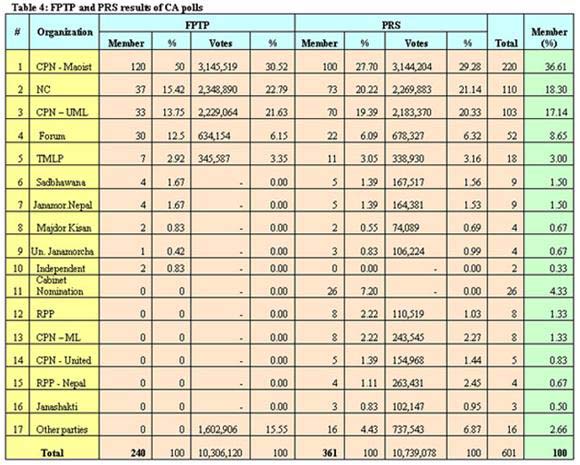

Maoist insurgency and the April Revolution was the awakening and assertion of minority identities which had remained dormant or suppressed. This has been reflected in the Constituent Assembly polls and may have far reaching consequences in the years ahead. The emergence of identity politics has also given a new dimension to the aspirations of the people of the terai. An analysis of the election results shows that the Maoists have been swift in giving representation to smaller groups. As also to women. This has also been made possible by the provision of 58% of the seats under a proportional representational system. It may be noted that in the Assembly women have a third of the seats. Those who may be considered to belong to depressed classes have similar representation. (The charts below indicate the strength of the political parties, votes received and gender and caste in the Constituent Assembly. The Maoists have clearly established themselves among younger representatives and women. Bahun/Chhetris - Brahmins/Kshatriyas - continue to have a disproportionate share of representation)

The 30% vote for the Maoists (the Nepali Congress and UML together sharing about 40%) may have been as much a vote for the party as a rejection of the others. The NC in particular is yet to internalize and accept the people's verdict and may not be averse to bringing down the Maoist led government. NC manipulations under Koirala leadership could pose a threat to the stability of the government as well as the constitution making process.

janjatis, then hardliners may reconsider associating with a multi-party democratic framework. Prachanda is still primus inter pares, perhaps not even that, in the ideological structure of the party. Possible hasty moves by hardliners cannot be ruled out.

Issue of induction of at least some Maoist cadres into the Nepali army remains yet unresolved and adds an element of uncertainty to the political scenario. While usual objections to inducting ideologically motivated cadres are well known and oft repeated, it is necessary for non-hardliner Maoist leaders to show some progress on induction as agreed upon before the elections. This is an area where India can give constructive advice. It must needs be remembered that the Maoists were not defeated by the Royal Nepal Army but chose voluntarily the democratic path while still in effective control of much of the countryside.

Madhesis have legitimate grievances about non-representation in the army. They now seem to want Madhesi induction as a pre-condition for inducting Maoist cadres.

The Youth Communist League remains. Matter of grave and understandable concern to other political parties and people generally. From the Maoist point of view, dismantling the body without some structured rehabilitation of its cadres is also not possible.

After two centuries of being treated as second class citizens, the Madhesis see a window of possibility in the 'new'

The demand for a single state of Madhes from West to East raises immediate suspicions among the hill people about the possibility of secession. This fear is a continuation of the ingrained belief that the Madhesis are somehow more Indian than Nepali by virtue of their language and dress. There is no unanimity in Madhes itself on the issue of one unit.

There are close familial links between Madhes and adjoining Indian states of Bihar and UP. In fact, in many villages, no distinction is made on the basis of nationality. This elementary fact has

to be taken into consideration by both national governments. There is lesson in the Sri Lanka experience vis-à-vis the northern Tamils. Similar development in Nepal with regard to Madhes could have far wider and more unsettling implications.

There are nexus between criminal groups in Bihar/UP and Madhesi elements. They are also involved in Nepal politics. This is a source of concern in Nepal. Additionally, there has been support from Hindutva elements in India for Hindu kingdom. Feudal elements in Madhes have been supportive of monarchy.

Recent communal incidents in eastern Madhes are disturbing.This has the possibility of introducing communal divisions in Nepal, hitherto absent.

There is considerable psychological dependence of Madhes on India which makes it all the more important for India to tender sober, constructive and practicable advice. It would not be in India's interest if separatism takes root in Madhes.

The palace will not regain old position. However, existing elite who feel threatened by the emergence of a 'new' Nepal may not be unhappy to see a roll back. In their own interest, however, they would work in co-operation with new leadership unless they see opportunity of destabilisation in conjunction with political elements unreconciled with change.

Thus far the army has conducted itself with propriety. Though the army leadership may have been, or are, inclined towards monarchy, this need not hold true of the soldiers who are in touch with ground realities and feelings. The new government has also treated the army with all due consideration. Even on the question of induction of cadres, the army has not been pushed. However, if there is a serious breakdown of governance due

Despite differences over years, Indian views would be held in respect by the Nepali army. There also exist personal and institutional connectivities (even though these should not be over estimated). These need to be utilised by India to ensure that army remains in line with the aspirations of the people.

In recent years, the West, notably the United States, has had increased interaction with the Nepali army. The implications of this would need to be carefully watched.

Hard-line elements of the Maoist leadership may want a certain degree of Chinese influence in the army as a counterpoise to western or Indian connections. This would have its own limitations, but nevertheless requires careful monitoring. (It may also be recalled that in the past royal regimes

in Nepal have not been averse to military co-operation with China)

It needs to be noted that for nearly two centuries, the Nepali army has had no cause to distinguish itself in war. There is an inclination to equate the valour of the Gorkhas in the Indian army (itself a projection by the British with political overtones) with the abilities of the Nepali army. Despite every support, the then Royal Nepal Army made little headway against Maoist insurgents. Further, we do not as yet know to what extent the rank and file of the army have been affected by the wave of expectations which have been sweeping Nepal. In 2006, there were instances of the wives of soldiers publicly demonstrating against the monarchy doing, as they said, their duty to the country as their husbands did theirs to their regiments.

Besides elements noted above, players in the present situation in Nepal would also include an increasingly assertive civil society and a remarkably courageous press. They played a significant role in the period following Gyanendra's take-over in 2005. They can be described as nationalist in outlook.

The most desirable scenario would be a successful conclusion of the peace process. This would imply:

(a) Acceptance by all players that change has been mandated by the people, that change is necessary and that change has to come about by peaceful means. There has to be broad agreement on the nature of change which would be reflected in the new constitution. Abolition of monarchy was only a necessary first step. While overall there has been an admirable spirit of accommodation in the past few years, fissures in this approach are now increasingly visible.

(b) Nepal emerging as a federal democratic republic where power moves from a Valley centric and Valley controlled administration to the real stakeholders, the people. Necessary also to ensure that the creation of federal units do not hamper overall economic progress. Assertion of the rights of minority groups can be a heady wine if it is not used constructively.

(c) The aspirations of the various groups who have felt deprived being met in economic, social and political

terms. Devolution and decentralization would be necessary. Emergence of an inclusive society.

(d) Uninterrupted development of Nepal's natural resources, particularly water related. Close co-operation with India is a pre-requisite.

(e) Planned development of tourism with maximum benefits to the local people (not for tour operators, or for westerners or Israelis to have an inexpensive holiday, as often seen presently. Or for Indians with wads of notes in casinos)

(f) Nepal becomes a hub for international conferences.

A less desirable, but entirely possible scenario is the politics of Nepal slipping back into the earlier manipulative and corrupt politics. This may be the preferred option of existing vested interests both in Nepal and abroad. Maoist elements themselves may fall prey to temptations in the name of accommodation (as being implied by purists/hardliners in the party). The reaction of the people, who have tasted the power of their numbers and resolve as demonstrated in 2006, may take time to crystallize. People have been and would be patient, but not indefinitely.

The army would have a major role in either of the less desirable of the scenarios suggested.

Indian national interests in Nepal centre round questions of development of water resources and several facets of security.

A major part of the downstream discharge of the Ganga is contributed by flows either originating in Nepal or transiting Nepal from sources in Tibet. These are, notably, the Kosi, Gandak and Karnali systems. Nepal has an achievable hydel potential of nearly 45,000 megawatts. Because of the terrain, Nepal provides the best, if not the only, options for downstream flood control and dry season augmentation. Agreements between Nepal and India in the fifties led to barrages on the Kosi and the Gandak, and later at Tanakpur. Such barrages provide only a minute fraction of the advantages which more ambitious co-operation could provide. Though an effort in this direction was made with the Mahakali Treaty in early 1996, there has been no progress. There has been resistance in Nepal to move forward. Ironically, as of today, Nepal is a net

importer of electricity from India. (Possible future course of action will be addressed later in the paper.)

India's security concerns vis-à-vis Nepal has several dimensions.

China has not aggressively promoted its presence in Nepal. However, existing roads, roads being built as also the possibility of extension of a rail line to the Nepal border, does provide for the possibility of substantially increased Chinese presence/activity in Nepal if Beijing so wishes. Nepal itself has adroitly used the China card vis-à-vis India, even though it is recognized that an intimate relationship with China is neither feasible, nor perhaps even desirable. India possibly needs to appreciate that there could be legitimate Nepali desire to cultivate a close and co-operative relationship with its large and powerful northern neighbour.

China may be expected to continue a policy of engagement with Nepal in projects and other activities which consolidate its position. Actual commitment of financial resources may be limited.

As in the past, China would not be averse to availing of low cost options to take advantage of anti-Indian sentiments wherever available.

China may like to see Nepal as a gateway to South Asia.

As is evident, China would like to woo the new dispensation in Nepal. Our reaction has to be measured.

Pakistan's objectives in Nepal are limited to making use of the open border to promote its subversive activities in India. Even the major

With its own Maoist problem, many in India have been concerned with the Maoist performance in the Nepal elections and accession to government. It could just as well be argued that the transformation of leftist insurgents to votaries of parliamentary democracy could have a positive effect on the Indian Maoists. Unless one foresees the successful establishment of a radical, ideologically motivated, reckless left-wing government in Nepal, there is no possibility of a nexus between the Maoists of Nepal and Indian Maoists to the detriment of the Indian state. (Any attempt to establish such a state in Nepal would be self destructive) It is noted that within the Maoist establishment in Nepal, there is currently talk of renaming the party simply Communist Party of Nepal. It is arguable that a successful Maoist government in Nepal could be used as

an example to Indian Maoists to move away from their present strategy.

The open border is a matter of concern, and also perhaps of opportunity. Given its importance particularly for the immediate cross border connectivities, it cannot be converted to a closed border. We also need to bear in mind that deployment of BSF and border fencing on Indo-Bangladesh border have not stopped either smuggling or illegal migration. Indo-Nepal border is an even more difficult proposition. What is necessary is regulation and development. (Further suggestions later in the paper)

India is Nepal's largest outlet for foreign employment. Number of Nepali nationals working in India would run into millions. Some would be seasonal work, some permanent. This issue needs to be considered, particularly in the context of the revision of the 1950 Treaty.

There is resentment at least among some sections of Nepali speaking Indian population that large scale entry of Nepali nationals into India and their alleged negative activities is giving a bad name to Nepali speaking Indians. How this progresses needs to be tracked. In this context there have also been demands from Indian Gorkhas for terminating the 1950 Treaty and its clause of national treatment.

Nepal has several concerns vis-à-vis India. While India may consider some to be unfounded, even as perceptions they need to be taken note of for future development of relations. These may be listed as follows :

Nepal is conscious of and resentful of dependence on India. The often patronising Indian attitude does not help.

In this context, it is worth recalling two recent observations. A well educated Nepali who studied in JNU under a grant of the BP Koirala Foundation, said that India considers Nepal solely a source of man-power (with the palace as its prime agent). An acknowledged author and activist recently commented that India cannot make up its mind on whether to treat Nepal as one of its neglected north-eastern states or as a sovereign country. Justified or not, reasons why such views should be held require assessment.

There is understanding and appreciation of the depth of religio-cultural links. But this also leads to fear of being assimilated. Such

Following calculated anti-Indian propaganda by the palace from the sixties, there is a belief that the treaties/agreements between Nepal and India are in some way 'unequal' and not conducive to Nepal's interests. This feeling has been internalised and used for political purposes by all political parties in Nepal. There is resentment in particular with regard to agreements on rivers, now further underlined by the Kosi breach.

The very large Indian share in Nepal's trade, tourism and investment is used by interested parties to promote apprehensions about India etc.

Negative views about India are held largely by interested parties.

There is understanding of the employment opportunities available in India. These opportunities are crucial for Nepal's economy. This is, however, taken for granted.

There is frequently a disconnect between interests of the Nepali people

and stated political attitudes.

Familial connectivities exist with both Madhesis and the hill elite. The former underline this strongly.

Acute consciousness of dependence on India for links with outside world. This was accentuated by restrictions imposed by india in the eighties.

Public statements of preferences in Nepali politics, or denigration of developments, as seen both from the Indian establishment and major Indian political parties, can only confirm Nepal's worst fears about Indian intrusiveness in their affairs.

It is believed, with some basis, that India influences political developments in Nepal. The 12 point peace accord is a recent example. The problem is that Indian assistance/advice is not imposed but usually follows Nepali requests. Nevertheless, adequate note does need to be taken of Nepali nationalist sensitivities.

India has substantial assets in Nepal. They may be summed up as follows:

(a) Cultural and familial connectivities form a deep bond between peoples of the two countries.

(b) There continues to be close ties between Madhesis their immediate neighbours in Bihar and UP. Nationality may well be considered secondary to marriage ties. With the recent changes in Nepal, the Madhesis may not feel as left out of the political mainstream as they have in the past and may take pride in being associated with the governance of Nepal. Ties with the southern neighbour will, however, continue.

(c) There are also familial connections with the hill elite (including with former royal family), business classes and others at various strata of society.

(d) Besides serving soldiers, there are over hundred thousand Gorkha pensioners. They form an influential part of Nepali society even in remote regions with positive attitude towards India.

(f) India is the natural source of investment in Nepal.

(g) Connectivity with the outside world (which cannot be replaced by trans-Himalayan Chinese facilities even if they develop substantially) provides India with natural leverage.

6. BUILDING BLOCKS FOR THE FUTURE (on the assumption of a steady progress towards consolidation of the peace process)

Nepal is in the process of far-reaching transition from a system and government of the few in the Valley to an inclusive polity which will perforce have to reflect the interests of people hitherto on the fringes. Existing players will surely remain, but as surely new players would emerge on the political chessboard. Even the full contours of the changes that could or will take place cannot be discerned at the current period of flux. Whether this 'revolution', the first of its kind in South Asia, takes place smoothly or stumbles along the way, cannot yet be forecast. All one can presently say is that over the past three years the political classes and the people of Nepal have acted with wisdom at moments of great stress and apparent breakdown, contrary to many dire forecasts. Thus, so far the signs have been largely positive. There are some signs of erstwhile major political parties wanting to put the clock back. But this could be largely the wishes of ageing leadership. It is likely that younger elements in such parties would be increasingly impatient if change is thwarted. The Maoists are yet to develop

The present desire for change in Nepal, however, does provide India a unique opportunity of recasting the substance of Indo-Nepal relations in a fresh mould. The substance and the content of the relations have never been in any doubt. But the approach would have contributed to many bottlenecks and the failure to realize the full potential. The following areas would need attention and appropriate pursuit:

It is well known that influential elements in the machinery of the Indian state as also in the army and others were supportive of the continuation of the monarchy, in some form at least, until developments in Nepal made this no longer possible. An erstwhile ruling party in India publicly displayed distress at the end of the Hindu monarchy. It is important that there are no mixed signals, at least from anyone associated with the Indian government, that India understands the Nepali people's desire for change and stands fully behind them. The manner of projection of this approach is no less important. We

Maoists have been underlining the 'unequal' nature of the treaties signed with India, with particular focus on the 1950 Treaty. This has also been a common theme with other political parties. This Nepali mind-set has contributed to the tendency to blame India for most of Nepal's problems. India's approach to this question has been generally aloof, while we have, in principle, agreed to renegotiate.

The reality probably is that the treaties, particularly the 1950 Treaty - as its implementation has evolved - are of greater advantage to Nepal than to India. The security aspects of either the 1950 Treaty or subsequent understandings have long since fallen into disuse. The only aspect of the treaty which is still operational is with regard to national treatment, where Nepal is clearly the beneficiary. The employment of Nepali nationals in Indian state services flows from a decision of the Indian Home Ministry which predates the 1950 Treaty. The agreement of the induction of Gorkha troops in the Indian army pre-dates

independence. The decision on currency exchange was separately reached. The 1950 Treaty may be the most prominent, but does not by any means encompass the full range of the arrangements which define Indo-Nepal relations. While there should be care in not humiliating Nepal in the process of de-mythifying aspects of Indo-Nepal relations, India must ask for a fresh look at all treaties and agreements in keeping with signals emanating from Nepal over the years. We do have a tendency to give the impression that we know what is best. This has to avoided. Nepal must also know that there cannot be cherry picking in the process of renegotiation and the interests of both parties have to be taken on board. While scrupulously acknowledging Nepal's sovereign right to take sovereign decisions, we would need to convey that Nepal would be responsible for the consequences of its sovereign actions. It must be ensured that our views on possible contentious issues, and the implications of future decisions, are known to Nepali civil society and the media. It would be an error to deal with individual agreements and arrangements in a piecemeal manner. The essential problem is not of India having deliberately short-changed Nepal (though India may undoubtedly have been in error of judgement on various issues). The issue is political where the Nepali political classes have found it useful to accuse

Nepal is particularly sensitive to the question of the development of water resources, partly perhaps because it sees this as an area where it holds an upper-hand vis-à-vis India. We need to acknowledge that unlike the situation half a century ago, today Nepal does have a body of experts who can be engaged in constructive discussions. Also, some of the certainties that would have motivated, for instance, the construction of the Kosi barrage or the proposed Kosi high dam are now considered open to question. Within India itself there are sharp divergences of view on the damming or training of rivers. We should be willing to take a fresh look at existing agreements (noting that the Mahakali treaty has not moved in nearly thirteen years). Nepal must needs have greater sense of involvement and participation in future projects.

Except for a brief half-hearted period in the eighties, India has not been forthcoming on the question of associating third parties in the development of Nepal's water

In recent years there have been comments in Nepal suggesting that Nepal has been losing time and money in not developing water resources and the example of Bhutan's fruitful co-operation with India has been quoted. There is thus some body of opinion favouring co-operation with India which could be sensitively cultivated. Our first option for the future should be to offer Nepal generous terms for the utilization of its water resources, not only for power but for flood control and dry season augmentation.

To avoid any future misunderstanding, it would be necessary to proceed on future agreements with complete transparency, ensuring that Nepal's

civil society is always fully on board with regard to the implications of proposed movement as also the consequences of non-action. With Nepal presently undergoing massive power cuts, there should be a better grasp of the consequences of decades wasted.

A recent welcome development has been the entry of private Indian players in the development of hydel resources of Nepal. This trend could be encouraged. We should also concentrate on smaller projects in relatively remote areas where the benefits are seen to accrue directly to local people.

Largely because of the Valley centric governance over the decades, we have found a degree of comfort in developing and using personal linkages. This is even more true of the Nepali side. Consequently, Indo-Nepal relations have lacked the objectivity of a more formal state-to state relations where the interests of the state remain paramount. With the dispersal of the levers of power in Nepal, it is now possible to develop relations as between two sovereign states, with due accountability. (This is not to suggest that personal linkages are not important, but to assign it only its appropriate place)

The approximately 30,000 Nepali nationals (so-called Gorkhas) in the Indian army and the over 100,000 Gorkha pensioners are and will continue to

Even a few decades ago connectivity between east and west Nepal would have been through India in the south. This has changed with the construction of the East-West Highway. However, as seen recently after the breach of the Kosi embankment, alternative routes through India can become necessary. The construction of a east-west railway line through the terai would have enormous advantages not only for Nepal but also significantly for India, permitting direct access to Siliguri (and hence the north-east) from the west, avoiding the present circuitous route through Bihar.

While there is need to be mindful of the connectivities being built or

The business community in Nepal has not always acted in Nepal's interest (eg. importing goods against dollars for either smuggling to or exporting to India as Nepali products). We would need to selectively support their ventures with India where this leads to greater connectivity and integration. Indian investment either in private or public sector should be encouraged. This could have great possibilities once Nepal's hydel potentials start being realised. Every possibility of integrating the economies of the two countries with a band of stakeholders should be explored. In a sense this already exists. A main stumbling block is the 'trading' mentality of influential Nepali businessmen who look for opportunities of quick profits by exploiting trading regimes and are not interested in creating long-term connectivities. Our planning process should explore the possibilities of Nepal's development and the kind of inputs which would be required from India.

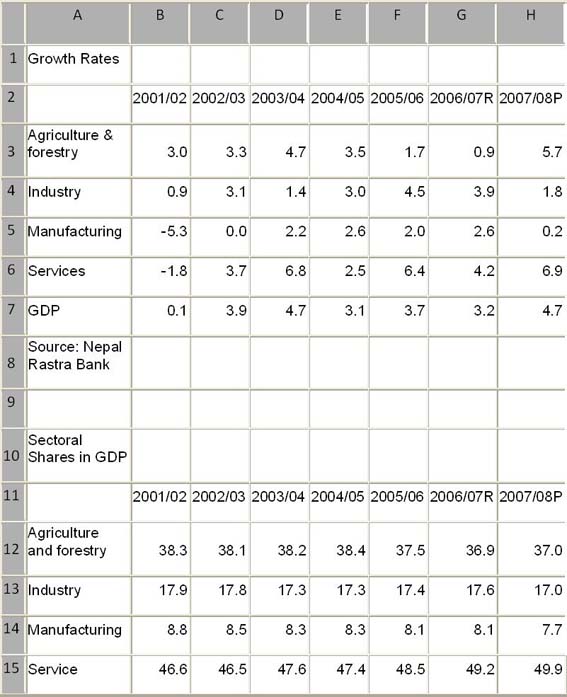

The chart below indicates the primacy of agriculture in Nepal's economy. If

hydro-electric potential is utilized, it should be possible to substantially increase the share of industry and manufacturing. Energy should not be seen only as an export commodity but a means of value addition in industry (for instance in the production of energy-intensive aluminium). A holistic view of Nepal's economic potential in collaboration with India would need to be undertaken.

A genuinely nationalist Nepali civil society and media (as against those who equate Nepali nationalism with an anti-Indian posture) is in evidence with the emergence of a genuine middle class in Nepal. We are likely to see greater number of Nepali nationalists who may judge issues on merits rather than be unduly influenced by pre-conceived notions. They could be our ally in developing a wholesome relationship with Nepal. There is a significant role for our public diplomacy in promoting understanding and exploring future possibilities.

The open border would feature increasingly in our relations. It is both

Regulation of the border is essential. This can be done only after the two countries mutually identify the present problems and decide on correctional steps. There are security issues on both sides. For India it could be ISI activities or the smuggling of currency. Nepal would have concerns about cross-border activities or co-ordination of criminal elements. Clearly, open border cannot continue to denote unregulated border. One way forward could be to have integrated border development programmes. Besides bringing greater prosperity, it would give local residents an active stake and interest to see that undesirable activities do not take place. There would be human issues involved in greater regulation and the effort has to be to cause the least disturbance to links between peoples while ensuring a larger quantum of security. India may also consider discussing with Nepal a time-bound plan for the regional development of the terai and an equal adjoining area of India in Bihar and UP.

With greater openings available both within and outside the country, the number of Nepali students studying in India would appear to be on the decline. It would be in our long term interest if Nepali students do pursue studies in India. The fee structure for Nepali students and what additional facilities could reasonably be provided should be assessed.

While these suggestions assume an orderly progression in Nepali polity, it is possible, as noted earlier, that there could be a period of serious disorder and civil strife. While our basic interests in Nepal may remain constant, our reactions would have to be tailored to exigencies. Whatever the situation, we would have to be guided by certain basic principles. One would be that the territorial integrity of Nepal is important. The Madhesis should have no illusions that India could be counted upon to support a separatist agenda. Equally, the people of the hills have to understand that legitimate Madhesi aspirations would have India's moral support. We would also need to walk a fine line between possible protagonists of 'law and order' and social and economic justice for which the Nepali people have struggled and which they have endorsed in the last elections. Essentially, we would have to be in tune with the interests of the people at large and not with interest groups with a limited agenda.

Back to writings